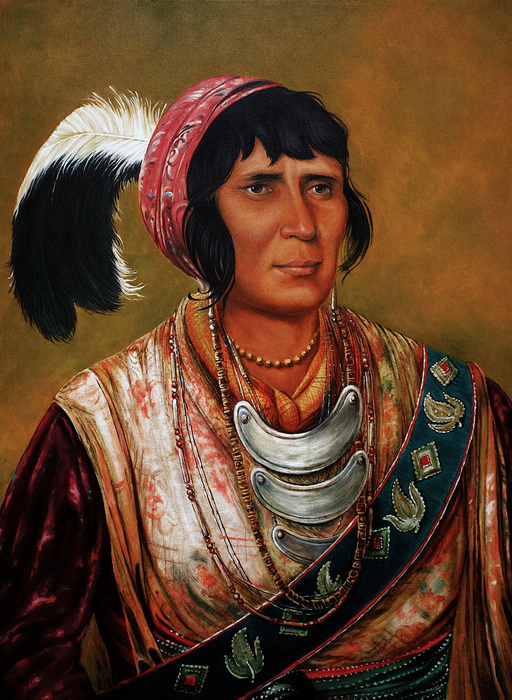

Chief Osceola

Osceola (Billy Powell)

Medicine Man and War Chief (1804-1838)

Osceola (ah-see-oh-la), William ‘Billy’ Powell, 1804-1838, was a Medicine man and War Chief of the Florida Seminoles during the Indian removal from Florida to unsettled U.S. territory in Oklahoma during the early 1800s. His significance in the academy, and the social sciences is linked to issues related to Native American identity and the political relationship between Native Americans and the U.S. government. Significant as well is his historical relationship to African slaves and contemporary African Americans’ tenuous relationship to Native American tribes—the Seminoles in particular, but also the Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee, and Chickasaw, who were removed from their original homelands in the southeastern United States to their present, primary home in Oklahoma.

Osceola is seen as a major figure in securing the rights of Seminoles and other native peoples during the colonial period—not through signing agreements and treaties with agents of the U.S. governments, as some tribal leaders had done, but through guerrilla warfare tactics that kept the U.S. military at bay for a long time, slowing the removal of Seminoles and the taking of Seminole lands. Osceola has also been viewed as a symbol of the ancestral mixture that formally, and informally, linked African peoples to the Indian tribes, a link that fuels contemporary claims to tribal government benefits.

The Seminoles in Florida were remnants of other Indian tribes that fled to Florida and established a lifestyle, culture, and politics that were indigenous and self-governing. Osceola strenuously objected to the United State’s offer to buy Seminole Florida lands in exchange for removal and settlement to open territory west of the Mississippi. Though his position differed from those of many of his tribal brethren, he found allies among another group of wanderers who had fled to Florida—free Africans and fugitive slaves who had several years before merged with the Florida Seminoles. These freedmen and fugitives—referred to by the Seminoles as Black Seminoles and/or Estelusti—joined the faction of Seminoles led by Osceola in opposing relocation, fighting alongside them in the Seminole Wars.

Although these “Black Seminoles” were loyal to the Seminole tribe, adopting many of their customs, intermarrying, and settling with them in the new Indian Territories in Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana, and other surrounding states, neither the Federally Recognized Seminole Tribal Governments nor whites during that period recognized them as official tribe members. Later, when the Dawes Act of 1887 required a census of Native American tribal members, Black Seminoles— referred to as Freemen—were counted as part of the tribal role, and received allotments of tribal lands. As a result of Jim Crow laws, enacted after Oklahoma statehood, Black Seminoles were physically separated from their Seminole tribal brethren and their legal status as official tribal members was called into question. The ensuing controversy lasted until the present, in large part due to the refusal of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to grant official certificates of Indian blood to Black Seminoles not originally on the Dawes rolls. Blacks were officially enrolled as tribe members and recognized as such, by the federal government. In 1991, the federal government awarded the Seminoles $56 million for their Florida lands, but non-black members of the tribe claimed that the black members had no claim to share in the award. This prompted black members of the tribe to file suit in federal court; in one argument, they pointed to the original relationship their ancestors had with Osceola (and one of his wives who was African descent) and their loyalty in fighting with him as a reason that they should be recognized as full tribal members.

In 1808, Osceola and his mother moved to Florida. They were associated with the Florida Seminoles, and with them Osceola fought in the War of 1812 and in 1818 against American troops under Andrew Jackson. By 1832, Osceola was living near Ft. King in Florida. Apparently, he was not hostile, for he was employed occasionally by the Indian agent to pacify restless tribesmen and by the military for scouting purposes for United States surveyors in recording Florida’s boarders. Such activities gradually brought him to prominence among the Seminoles.

In 1832, however, the United States government was under pressure to move the Seminoles west of the Mississippi River. Some Seminole chiefs were persuaded to sign a treaty of removal. Osceola opposed this, as he did a similar agreement made in 1835. Most Seminole chiefs signified their disagreement by refusing to touch the pen; Osceola did so by plunging his knife into the paper. He was arrested for this defiance. To secure his release, he pretended that he would work for approval for the treaty.

Osceola and his warriors brutally murdered the Indian agent Wiley Thompson with the very gun that Thompson gifted Osceola, in an attempt to appease Osceola, prior to releasing him from a military stockade. Osceola took punitive action against any who cooperated with the white man, and stood as a national manifestation of the Seminoles’ strong reputation for non-surrender.

Elegant in dress, handsome of face, passionate in nature, and giant of ego, Osceola masterminded successful battles against five baffled U.S. generals ion December 28, 1835. For the following two years, Osceola, with a mixture of American native warriors and escaped slaves, succeeded in winning most of the battles he and his warriors entered into during the next two years.

The first of his major battles occurred when Osceola’s forces killed Maj. Francis L. Dade and 110 soldiers. Days later, with 200 followers, he fought against Gen. Duncan L. Clinch and 600 soldiers. August 16, he almost overwhelmed Ft. Drane. Osceola’s fight was so successful that it led to widespread public criticism of the U.S. Army, especially of Gen. Thomas S. Jesup, which solicited German Hessians to murder Seminole elders, woman and children in the most brutal manner one could possibly imagine.

Osceola was honored internationally for his policy of only being at war with United States Military personnel, but would never kill women or children. He was often quoted as saying “we are at war with United States soldiers, not woman and children.”

The United States Army captured Osceola, on October 20, 1837, under a white flag of truce, to talk peace. At the time of his capture, he was very ill. This event remains today, one of the blackest marks in American military history.

While Osceola was incarcerated at Ft. Marion, Florida, he discovered that the United States Military had discovered where Harjo town was located (the secluded sanctuary for Seminoles elderly, women and children) and had ordered General Hernandez of the U.S. military to lay waste of Osceola’s hidden sanctuary. Upon learning of this march to massacre his people’s elderly, women and children, he ordered a number of his warriors to escape from their fort stockade in an attempt to save his people from being slaughtered. Osceola’s escaped warriors were a day or two days late. When they arrived, they found a number of their women horribly dismembered, and their babies impaled on pointed stakes. However, 33 of Harjo tribal members escaped into the Everglades and avoided being captured and/or murdered. Decedents of these people still reside in the very place that Harjo Town was laid to waste.

Osceola, his family, and warriors were removed from Ft. Marion, FL, and transported to Ft. Moultrie, South Carolina. He died there on Jan. 30, 1838, of a form of ‘strep throat’. Osceola’s death in prison at Fort Moultrie, SC, was noted on front pages around the world. In 1838, he was the most famous American Native.

Shortly after Osceola’s death, his mother, wives and daughters were placed on a boat to place them on the Trail of Tears, however, prior to reaching Oklahoma, they escaped into the Arkansas Ozarks.

For an extremely accurate portrail of the life and times of Osceola, read the fascinating book: ‘Light A Distant Fire’ by Lucia St. Clair Robson